MOBILITY ON AND NEAR POTOMAC RIVER

The waters of the Potomac were the first roadways known to Charles Countians. It was a roadway that needed no building, it never called for repairs, it came to every main landing. It so established itself in the people’s lives that supporters of land roads had great difficulty in ever getting them cut through the forest, much less built, or improved, or repaired.

Water travel held a practically exclusive sway along the river shores during the early years. The first roads were not highways but mere private roads leading from the tobacco barns in the fields down the hill across the bottoms to the river landings. They were referred to as “rolling roads.”

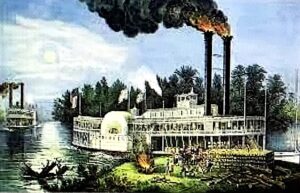

The first country roads were built and maintained by tax money or physical help in kind. County tax monies were used to employ road superintendents and to furnish road equipment and wagons. Farmers and merchants, and their tenants and hired hands supplied the labor. Travel by sail was dependent entirely on wind, weather, and tidal current. In the early 19th century, steamboat services new invention made water transportation faster and more reliable. However, there are very few records of sailing vessels taking stranded passengers from steamboats whose wood-fired engines failed to function correctly.

Steamboat service in Charles County waters began in June 1815, with a ferry from Washington to Potomac Creek, Virginia, in conjunction with stagecoaches to Fredericksburg, Virginia, for Richmond and the south. In the day’s fashion, Charles Countians obtained transportation to the nation’s capital by using tall semaphore signals ashore to attract the captain’s attention. If nearby wharfage were not available, passengers would be transported by rowboats to meet the steamer, boarding in the main channel.

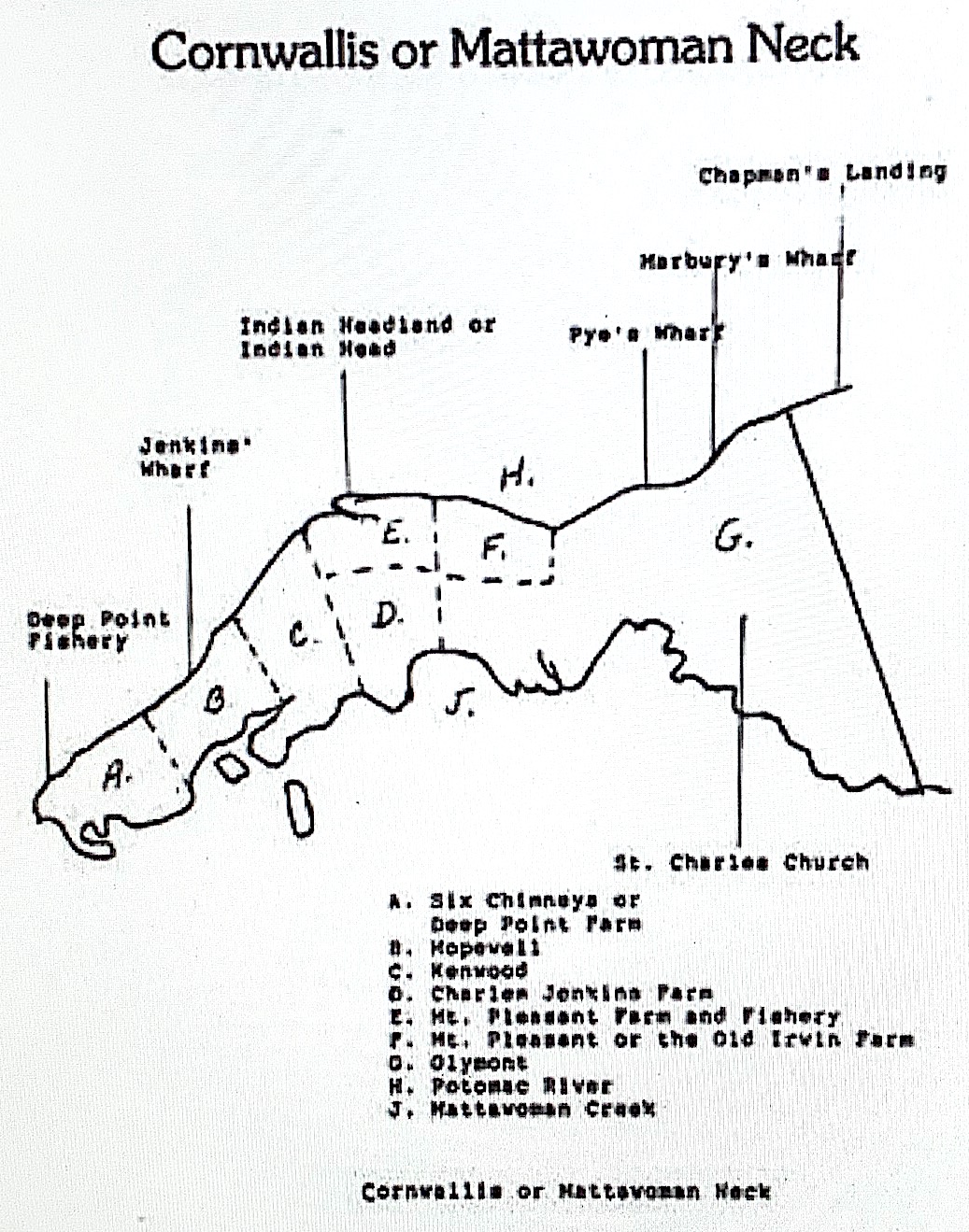

By 1800 regular scheduled service began between Norfolk and Alexandria, with stops at the river wharves upon signals made by the passengers. Passengers demanded better service, resulting in the 1827 establishment of the Washington, Alexandria, and Georgetown Steam Packet Company to service the many wharves from Marshall Point southward to Rock Point. Their first steamer was the Fredericksburg; later vessels, the Franklin and Columbia until 1874. Other ships to follow were Baltimore, Maryland, and the Diamond State. In 1860 Saint Nicholas was added, only to be captured by the Confederates the following year off Point Lookout; it was converted to a privateer and sunk at Fredericksburg.

Expanded business brought more steamers, with new Washington & Norfolk Steamboat Company operating OSCELA twice weekly on the circuit between these two cities and Baltimore.

The Civil War virtually stopped all private steamboat activities. Vessels were placed under Government charter by the Army Engineers, continuing to run many Charles County Landings under strict surveillance, as most of Southern Maryland was anti-Union in sympathy. In 1861-62 the Confederates almost completely blockaded the river, causing stoppage of all traffic for six months. Among the few steamers permitted to operate were the Planter and Keyport, owned by different companies in Washington and under a Government charter.

Mail was delivered before the Civil War by contract with Washington & Fredericksburg Steamboat Company, running from Washington to Aquia Creek, Virginia. The ships would stop twice daily at Marbury Landing (the lower of the two Glymont landings) and Sandy Point, using steamers Baltimore and the Mt. Vernon.

After the Civil War, the Potomac became the most convenient and economical highway to the “outside world” (until the 10930s) due to the geographical isolation caused by the two rivers, Patuxent and Potomac.

A typical advertisement in Washington, Alexandria, and Charles County Newspapers read:

The steamer MAJESTIC is a modern steel hull passenger and freight-carrying steamer and is practically new. Her state-rooms and saloons were new, and her main deck was entirely remodeled to fit her for the Potomac route in which she is employed. Her 42 staterooms are all outside ones and are furnished with brass beds or two metal berths and all the latest equipment. Numerous and skillfully arranged electric (or gas) lamps make the MAJESTIC rooms and saloons very bright at night. And airy apartments and a roomy Smoking Lounge are to be found on the hurricane deck. Competent critics pronounce her the most handsome and most comfortable steamer ever employed on this route. The equipment of the steamer is of the latest type and is complete in every particular.

The timetables shown give the steamer time to arrive at and depart from the several many landings, but it is not guaranteed. Bicycles, when accompanied by owners, are carried free at the owner’s risk. Baby carriages must be checked at a charge of 25 cents. Staterooms are $1.00, $1.25, $1.50, and $2.00 each according to location and size. Two persons are accommodated in the $1.00 and the $1.25 rooms; three persons may occupy them.

Several steamship companies were serving Charles County for many years after the Civil War. The Potomac Ferry Company opened to Charles County in 1865 with the steamer WAWASET, which ran until 1873, at 11:30 a.m., this vessel crowded with passengers and freight left Riverside Wharf for Chatterton’s Landing across the river, when in mid-channel it burst into flames; within eight minutes, 76 persons died.

Firemen aboard the steamer sounded the alarm that the steamboat was on fire. Because the boat was made out of wood and was very dry at the time, the fire spread very quickly. Captain Woods, while in the pilot’s house, attempted to steer the boat towards shore. Unfortunately, the steering ropes caught fire, and the ability to navigate the ship was lost. Communication between the forward and rear parts of the boat no longer functioned. Regrettably, those passengers in the front could not reach their lifeboats at the back of the ship. The fire spread so quickly that the lifeboats would have been of little use. The deck broke under the weight of the horrified passengers and sank. The origin of the fire prevented passengers from reaching boats and life jackets aboard the Wawaset.

WAWSAT

As the boat drifted close to the shore, the engine suddenly quit. Many passengers jumped from the ship, thinking they’d hit land, but what they heard was the grinding halt of the motor. Most disappeared and drowned in the deep water. Many aboard could not wait for the safety of shallow water; fire forced them to jump from the ship.