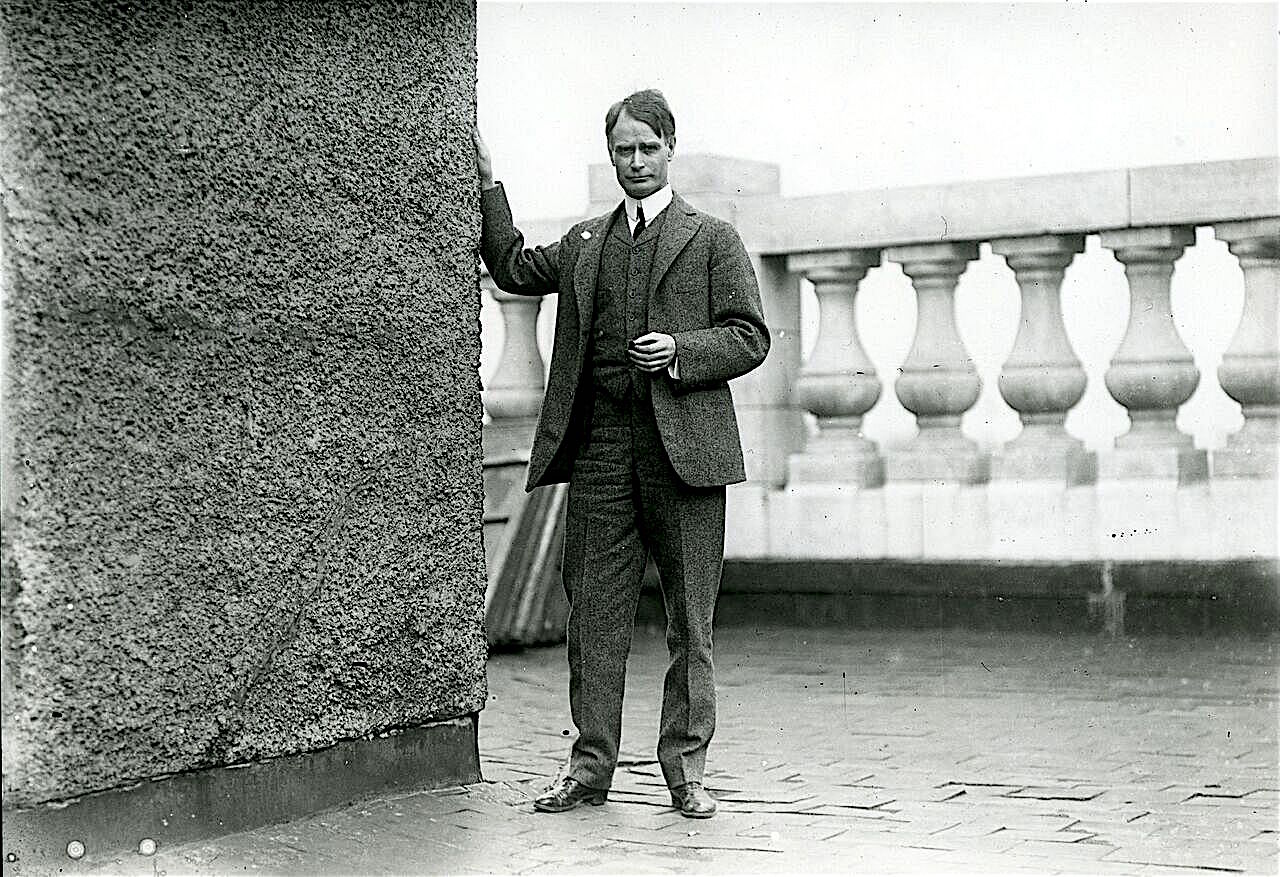

John Harry Shannon (AKA “The Rambler”)

J.H. Shannon traveled many miles on horseback, taking hundreds of pictures from Washington, D.C., Virginia, and Maryland. His articles written in the Evening Star and The Sunday Star gave its readers a glimpse of other towns and their way of life during earlier times.

The “Rambler” left us a roadmap to follow and a history of Southern Maryland. Founded on December 16, 1852, and closing on August 7, 1981, the Evening Star covered over 130 years of American history from within Washington, DC. From publisher’s information: Until its demise in 1981, The Evening Star was universally regarded as the “paper of record” for the nation’s capital.

Ronald Reagan’s words appeared on the front page of the August 7, 1981, issue of the Washington Evening Star. The most significant piece of news that day was the end of a 128-year-old Washington institution—the story of the newspaper’s demise.

John Harry Shannon was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on April 3, 1869, and was employed in the newspaper business until his death February 12, l928. “The Rambler” became his nom de plume after the success of his weekly series of articles in The Sunday Star from 1912-1927. He was often seen exploring the area on either horseback or bicycle, always with his 5 x 8 view camera along.

The age of technology brought us the computer, which allowed us to surf the Internet and explore the different databases that contained relevant information about “Glymont.” The name endures, but the bands, dancing, and picnics along the Potomac River’s shady banks are forever gone.

Washington sent many travelers by various steamboats to Glymont to enjoy their weekends while enjoying the rides and games. Today, one rarely thinks of Glymont as a historical place.

Residents of Washington, D.C. went to Glymont on the Mary Washington, the Mattano, the River Queen, and other steamboats that knew how to navigate the Potomac. Thousands of young men and women who capered to the cadence of the fiddles at Glymont have passed into the land of shadows. The Glymont that Rambler is talking about no longer exists. Glymont was known as Pye’s landing for over two centuries. After the Civil War, the New Glymont Wharf welcomed visitors to the new amusement park the Rambler speaks fondly of above.

“The Washington Post covered the resort’s grand opening in June 1899. Thousands of “pleasure-seekers” took the short trip from Washington on the River Queen and the Kent.

Twenty years before, a select group of Washingtonians, including senators and representatives, went down to Glymont for a shad-bake.

In 1877, the steamer Pilot Boy took about two dozen guests, including some from the newspapers from the Seventh Street Wharf to Glymont. On the way, a saloon served beverages, and guests had an “elegant dinner.” Other events included yacht races and rifle shooting matches.”

A few families built homes during the early 1900s on the land that is now called Potomac Heights. Most of the land at Glymont was subdivided into lots for farming. Lumber was cut and transported by ships across the Potomac.

In 1884 the Upper Glymont Improvement and Excursion Company sub-divided the land and planted fruit trees, walnut trees, and Chesnut Trees. The Fruit Farms was located on Glymont by the Mattawoman Creek. Existing street names at that time were Park Street, Potomac River, Mulberry Street, Walnut, Champman Street, Linden Street, Orchard Street, Broad Street, Magnolia Street, P{opulat Street Cherry Street, Merytle Street, Laural Street, Division Street, Church Street, and Chestnut Street. There was a beautiful Hotel called Alhambra Heights Hotel Pavillion, Artillery Park, and Washington Heights on the bluffs above the water.

The Department of the Navy purchased a tract of land called Cornwallis Neck to make gun powder in 1890. The Naval Powder Factory was built by military personnel and laborers on the long and irregular land between the Potomac and Mattawoman Creek, generally called Indian Head.

The neck is about six miles long and from one to two miles wide. The high, wooded part at the Potomac and has been called Indian Head. White settlers moved into Indian territory and broke every treaty they signed. Eventually, the Indians left, but the name “Indian Head” remains. House and business line both sides of the street along with schools.

The shore was sandy, and where the grandfathers and grandmothers of many lively Washingtonians went in bathing are covered with large water-worn stones.

The wreck of the pavilion is no longer visible. Scattered through the underbrush that has grown up around the pavilion are the flying horses, their wooden carcasses, and weather-beaten metal cars that are no longer visible. These poor things were once gay steels that scampered and caracoled, bearing little boys and little girls whose children have since passed.

Near Old Glymont, there was a road that leads from the river shore to the top of the bluff, there connecting with a picturesque road appropriately called Cedar lane. Cedar Lane leads over vast stretches of level and tolerably fertile land that was tilled by the slaves of the Pye and Marbury families for many generations. Once, mail coaches traveled there, the mail being carried from Washington to Glymont by steamer, taken by stages for distribution through a large part of southern Maryland. The stagecoaches carried passengers as well as mail.

Glymont is located in Charles County, Maryland, and was listed as a town in 1800, but Glymont can be traced back to 1654. From 1800 to 1913, the St. Charles Catholic Church was at Glymont.

In 1654, Lord Baltimore granted 5,000 acres to Thomas Cornwallis. This grant was bounded by the Potomac River and the Mattawoman Creek. The third boundary was in dispute at the start. This disputed land was called Glymont (see map). Pye was involved in a second dispute involving the land called Glymont. In 1736 M. Pye won another legal case against the Indians who had encroached on his land.